Jim’s Guide for Unit 9: Monopoly

I had no ambition to make a fortune; mere moneymaking has never been my goal. I had an ambition to build.

I had no ambition to make a fortune; mere moneymaking has never been my goal. I had an ambition to build.

– John D. Rockefeller, founder of Standard Oil Company, a monopoly

One in economics, the other in politics, refuted the liberal dream of universal happiness

through individual competition, substituting monopoly and the corporate state, or at least movements toward them.

– Bertrand Russell, Freedom Versus Organization, 1814 to 1914,

At the start of this century in 2000, Bill Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft, was widely reported to be the richest man in America now. He’s still very rich and close to the richest, but not quite. But 100 years ago, at the start of another century, the richest man in America was John D. Rockefeller. It’s difficult to compare fortunes 100 years apart due to the effects of inflation, but some economists have estimated that Rockefeller’s fortune at its peak was perhaps 3-4 times as large as Gates’s fortune today. That’s a lot of money. Rockefeller wasn’t alone, though. Rockefeller’s time was known as the “era of Robber Barons”. Others accumulated huge fortunes: Andrew Carnegie,Thomas Edison, Cornelius Vanderbilt, J.B. Duke, and others.

How did these people accumulate so much money? One word: Monopoly. In the last unit we studied how the forces and conditions of perfect price competition keep firms from being able to actually earn economic profits over the long-run. Yes, a firm in perfect competition might make some economic profits in the short run if market prices are favorable, but price competition and entry of new competitors eventually put an end to the profits. But, under conditions of monopoly, a firm doesn’t have to worry about competitors. A monopolist doesn’t have any competitors. There is no competitor to undercut price. Truly successful monopolies are also able to prevent any future would-be competitors from entering the industry.

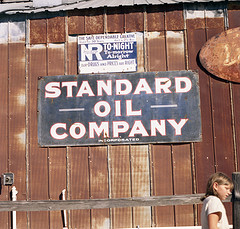

When monopoly conditions exist and the product is in demand by consumers, the monopolist can (and usually does) make extraordinary profits. In the late 1990’s, Microsoft controlled over 98% of the market for personal computer operating system software. That’s effectively a monopoly and it led to the huge monopoly profits that became Bill Gates fortune. In the 1890’s, John D. Rockefeller’s company, Standard Oil, controlled over 98% of the market for oil and gas in the U.S. Standard Oil’s monopoly profits became the source of Rockefeller’s fortune.

In this unit we will study monopoly. The objectives for this unit are:

- List the characteristics of monopoly and give examples.

- Explain and show, using both tables and graphs, how a monopolist determines the price and quantity that will maximize profits in the short run. Use tables and a graph to show the size of the profits or loss.

- Explain the dynamics of what happens in monopoly in the long run and explain and show graphically the long run equilibrium situation.

- Explain how well monopoly achieves social goals of productive efficiency, allocative efficiency, and innovation.

Monopoly: The Goal for Profit-Seeking Businesses

In the unit on Perfect Competition, I described the following “spectrum” of competitiveness:

In that unit, we saw how Pure Price Competition (Perfect Competition) led to a long-run outcome where firms don’t make any economic profits. Obviously, since firms and entrepreneurs want to maximize profits, they would rather not compete in Perfect Competition, if at all possible. In this unit we look at the complete opposite situation: Monopoly. In a Monopoly, there is no competition. A monopolist doesn’t have to worry about being undercut on price and the most successful monopolies don’t have to worry about new entrants into the industry lowering market price.

In that unit, we saw how Pure Price Competition (Perfect Competition) led to a long-run outcome where firms don’t make any economic profits. Obviously, since firms and entrepreneurs want to maximize profits, they would rather not compete in Perfect Competition, if at all possible. In this unit we look at the complete opposite situation: Monopoly. In a Monopoly, there is no competition. A monopolist doesn’t have to worry about being undercut on price and the most successful monopolies don’t have to worry about new entrants into the industry lowering market price.

For business firms (and their owners), Monopoly is the goal. A true monopolist maximizes profits by following the same decision process as other firms. In other words, a monopolist will follow the MR=MC logic to find the quantity to maximize profits. Likewise, a monopolist calculates profits as (P-ATC) times the Q sold. The difference is that a monopolist doesn’t have accept some market-driven price. The monopolist can set the price. There are some limits on how much a monopolist can charge (see below), but essentially a monopolist can pick his/her own price. this time, the conditions of the market result in the Monopolist making very large economic profits. What’s more, since one of the conditions is barriers to entry, the monopolist doesn’t have to worry about new competitors coming into the market and cutting prices (and thereby the profits!). The monopolist just keeps on making economic profits over the long run.

The Conditions of Monopoly

In a monopoly, there is only one firm. This one firm supplies the entire market. This one firm, the monopolist, is the market supply curve. There is no competition. But, for a monopolist to turn this lack of competition into truly large economic profits there are other conditions that must exist too.

Two conditions are necessary for a monopolist to be able to charge high prices and reap large economic profits. The first is that barriers to entry must exist and they must be strong. Usually, this means some kind of legal restriction or privilege that makes the monopolist the only game in town. In other cases, it means literal control over some critical resource. Barriers to entry prevent other firms from getting into this particular market. Since other firms cannot enter, there is no competitive threat and no reason for a monopolist to be restrained in pricing the product.

The other condition to making substantial economic profits, is a friendly demand curve of consumers. Ideally, the monopolist wants a substantial demand curve that is relatively inelastic for large volumes. An inelastic demand curve means customers are willing to pay substantial prices for a product they view as a necessity and that doesn’t have good substitutes. When demand is inelastic, it means consumers don’t have much choice – they feel they “have” to buy the commodity. It’s this inelastic demand combined with a lack of competition that gives the monopolist her power.

Monopoly, while very good for the monopolist, is very damaging to the welfare of everybody else. Indeed, monopoly can be so lucrative and so profitable, that some businesses will do almost anything to obtain it. As a result, most modern industrialized societies, such as the US, the European Union, Canada, and others attempt to control, regulate, or prevent unrestricted monopolies from occurring. Your book discusses how to control monopolies in the chapter on anti-trust (look it up in the index). We won’t study anti-trust during this semester, but if you have any interest in monopolies, particularly the Microsoft case, you might want to look at that chapter. It is entirely optional, though.

Analysis of Monopoly

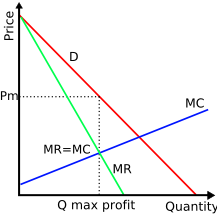

The analysis of monopoly is shown in the graph to the right here. I have omitted the ATC curve from this graph to help focus on how marginal revenue (MR) is different for a monopolist than for a perfect competitor. You might also notice that the marginal cost (MC) curve looks a bit different from the J-shapes you have seen earlier. Most monopolies are large enough that the we have simply “zoomed” in on the part of the graph where MC is upward sloping – it is still the same concept of marginal cost.

The analysis of monopoly is shown in the graph to the right here. I have omitted the ATC curve from this graph to help focus on how marginal revenue (MR) is different for a monopolist than for a perfect competitor. You might also notice that the marginal cost (MC) curve looks a bit different from the J-shapes you have seen earlier. Most monopolies are large enough that the we have simply “zoomed” in on the part of the graph where MC is upward sloping – it is still the same concept of marginal cost.

What is definitely different from what you’ve seen before is the MR curve and the downward sloping D curve. The downward sloping D curve is, in fact, the market demand curve. The market demand is the demand for the monopolist’s product since the monopolist is the only source for the product. Since market demand curves slope downward, so does the demand for the monopolist’s product.

Now it becomes important to remember the precise, technical definition of marginal revenue: marginal revenue (MR) is the change in total revenue when another unit is sold (Q is increased by one). We assume that a monopolist charges the highest possible price that still sells whatever quantity the monopolist wants to sell. The monopolist picks a quantity to sell. The monopolist then goes up to the demand curve (D) for that quantity, then goes over to the corresponding price. This is the highest price that will still sell all of that quantity.

Since the monopolist is selling at the highest price possible that still sells a particular quantity, then if the monopolist wants to sell one more unit (the marginal unit), then the monopolist must lower the price a little bit. When the monopolist lowers the price, it not only is lowering the price on that next unit, but it has lowered the price on all the units in that quantity. By lowering the price, the monopolist gains some revenue (the sale of the additional unit), but it also loses some revenue because it has to lower the price on the units it was already going to sell. This phenomenon means that when demand is downward sloping, the marginal revenue curve is also downward sloping. In fact, the MR curve will be underneath D and have twice as steep a slope. [note: students familiar with calculus may realize this is because MR is the first derivative of D].

So, the curves in the graph might look different from Perfect Competition, but that’s the only difference. The logic and analysis are still the same. To find the quantity that maximizes profits in the short-run, find where the MR and MC curves intersect, drop down and that’s the quantity that maximizes profits. Then, for that quantity, go up to the demand curve and look up the price – that’s the highest price that will sell that profit-maximizing quantity, and that’s the price the monopolist charges. To calculate how much profit is being made at that price, we need to find the ATC for that quantity and subtract it from the price.

Price Discrimination

The above analysis leads a simple monopolist to charge a much higher price and sell a smaller quantity than what would happen in perfect competition. But the monopolist makes substantial economic profits by being able to charge this higher price and make it “stick”. Still, some monopolists want even more. They figure if they can separate customers into two (or more) groups, they could charge the high price to customers who would have purchased at that high price. Then these monopolists want to charge a lower price to be able to sell an additional quantities to those customers who are really price sensitive. This yields even more total profits to the monopolist. This behavior is called price discrimination.

Barriers to Entry: The Key to Monopoly Profits

It isn’t enough to have a product that consumers demand and to be the only source of the product. For a monopolist to charge high prices and earn large economic profits for any extended period of time, the monopolist must be protected by barriers to entry. Sometimes, the sheer economies of scale of the technology needed to produce the product makes a sufficient barrier to entry. But the most reliable and the strongest barriers to entry depend on either gaining exclusive control of a critical resource needed for production or having the government prevent competitors from entering.

Some of the most successful monopolies have relied on gaining powerful control over some critical resource. For John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil, the key was exclusive deals with railroads that provided significantly lower freight rates for Standard Oil and higher rates for any would-be competitors. For Cecil Rhodes, the founder of the DeBeers Diamond cartel, the original key resource was exclusive rights to diamond mines in South Africa. Later he and Ernest Oppenheimer gained exclusive control over the wholesale marketing of diamonds in London and Belgium. Microsoft gained exclusive access to being pre-installed on computers by signing exclusive contracts with PC makers. The U.S. government later sued and convicted Microsoft of making illegal contracts with these PC makers, but by then the fortune and monopoly status had been achieved.

While the US government has, at times, fought monopolies such as Microsoft, Standard Oil, and American Tobacco, it also creates many monopolies. For example, an effective barrier to entry can be a patent issued by the government. In other cases, governments often grant exclusive rights to some firms and prohibit competition. For example, for over 80 years, AT&T had a monopoly on long-distance telephone service. For at least 60 years, until 1984, AT&T had a monopoly on all telephone service.

Results of Monopoly: Who Pays?

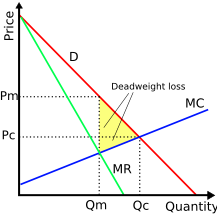

Monopoly is indeed very attractive to the lucky firm that achieves it. But, looked at from a social perspective, monopoly is definitely very un-attractive. The graph at the right compares the pricing and production quantities of a monopolist to what would happen in competition. As you can see, the monopolist earns the higher profits by charging a much higher price. Consumers must pay this higher price. Consumers also suffer because a smaller quantity will be produced. Some people who would have been able to afford a competitively priced product will not be able to afford the product and will have to do without.

Monopoly is indeed very attractive to the lucky firm that achieves it. But, looked at from a social perspective, monopoly is definitely very un-attractive. The graph at the right compares the pricing and production quantities of a monopolist to what would happen in competition. As you can see, the monopolist earns the higher profits by charging a much higher price. Consumers must pay this higher price. Consumers also suffer because a smaller quantity will be produced. Some people who would have been able to afford a competitively priced product will not be able to afford the product and will have to do without.

A monopolist also produces inefficiently. Monopolists do not produce at the lowest possible ATC, because they can maximize profits with a smaller quantity. Monopolies are also allocation inefficient because consumers aren’t really making the decisions on how much to produce.

Yes, a successful monopoly can accumulate enormous economic profits and private fortunes such as Standard Oil and Microsoft. Sometimes, these private fortunes are put to good charitable uses later. John D. Rockefeller endowed and started several major universities (Univ. of Chicago, Spellman College, Johns Hopkins, and others). Andrew Carnegie built hundreds of libraries throughout the US. Bill Gates has now pledged to use his fortune to fight AIDS and other diseases. But these fortunes didn’t come from nothing. These fortunes come from the higher prices that millions of customers had to pay because they didn’t have any choice. Any social evaluation of monopoly must take account of the opportunity cost of those higher prices and lost output.

What’s Next?

Most business firms might dream of being a monopolist, but realistically they can’t. Most products made by most firms have good substitutes. Entry is possible in most real-world markets, making long-term monopoly impossible to maintain. Nevertheless, most firms in the real world don’t surrender, give up, and resign themselves to a life in perfect competition. These firms find ways to carve out little “temporary” monopolies instead of competing on price. In the next unit, we take a look at this real-world phenomenon called monopolistic competition.

Ask five economists and you’ll get five different

answers (six if one went to Harvard).

– Edgar R. Fiedler

To finish this unit, be sure to:

- Read the textbook (see the Reading Guide for what chapters and pages to read in the textbook or other source)

- Take a look at any tutorials, videos, or articles in Closer Look

- Try the practice quiz

- Complete the worksheet assignment

- Complete the Graded assignments in your school’s Learning Management System

Download this page in PDF format

Download this page in PDF format